Vintage 2020, bad vintages and other X-Files

Whenever we ask ourselves about the importance of vintages in the world of wine, we have an opportunity to remind ourselves that wine comes from grapes. Those little berries that appear on the vines every year if nothing unusual happens, and which some ladies and gentlemen take care of, putting all their care and attention, and at a given moment harvest them and turn them into wine. Not by magic, but almost always by sweat and tears. The amount of sweat and tears (and uncertainties to which Pachamama subjects them), is usually inversely proportional to the ability to invest money in more hands, more chemical aids, and more technology, not always for the sake of higher quality or respect for the environment.

Somehow we have to understand that every year the vineyard (the weather and nature in short) gives vine growers and winemakers the tools with which to work, and that depending on what our objective is in thinking and creating a wine, we can get closer or closer to the identity of the vintage, resulting in wines with greater variability, or a more homogeneous product.

But then, will I not like my favourite wine next year?

Don't panic. Just because each vintage may be different doesn't mean that a winemaker, or a winery, is not capable of imprinting a style on its wines, a kind of watermark that makes us identify them, recognise them, and sigh with confidence every time we smell what we expected to smell.

However, the beautiful (and sometimes frustrating) thing about wine is that it is a living process. And besides being alive, it is very multifactorial. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to know for sure the degree of change in a wine from one vintage to another, which may be due to changes in aspects related to the vintage, or to changes in the winemaking process, either by the winemaker's own decision or by trying to get closer or closer to a certain trend. Thus, a wine that we remembered as very forceful, concentrated, heavy, a couple of years later, in a similar vintage, suddenly becomes a more fluid, more refreshing, lighter wine. It's not that they have put the vines on a diet, or put giant umbrellas in the vineyard so they don't get so much sun, but simply that someone has decided to do something different enologically, for some better and for others worse, using the available resources and technique.

A simile that we will all see clearly (although it may not amuse a fellow CraftBeerManiaco). To brew a beer, we can change the ingredients, temperatures and fermentation times, or the vessels in which we brew each batch. But none of these factors are going to be directly dependent on the calendar year (except for some very specific styles like lambic beers with ageing and vintage designation)

What is a good vintage and a bad vintage?

The question is for whom. A vintage that is meteorologically complicated, for example, a very rainy vintage, with many health problems, with a significant drop in production, can be a fantastic year for some producers who have had the luck and knowledge to overcome these problems, either by location or by having made the perfect decisions at key moments. And to top it all off, the harshness of this particularly cold vintage can favour longevity, give more freshness, even more finesse in some specific styles.

From the winegrower's perspective on the one hand, a good vintage will be one with a good weather balance, enough water (but not too much), enough heat, good thermal oscillations without surprises, cold when it has to be cold, and heat when we want the cycle of the plant to continue forward. Everything in the right measure and without overdoing it, as in The Price is Right. And most importantly, that we can harvest as many kilos of healthy grapes as possible, to reward the work of a whole year. If a winegrower takes his grapes to a cooperative, in many cases he will also be looking for the highest possible alcohol content (settlements are still made on a kilo/degree ratio).

From the winemaker's perspective sometimes, it is not even enough, and he will most probably look for fruit with higher concentration and better phenolic ripeness than industrial. So that we understand each other, he will look for more precursors of aromas and flavours and elements such as acidity or good concentration, rather than simply alcohol and more diluted grape musts typical of harvests with a lot of fruit on the plant. And sometimes for that it is necessary that the plant is not so "comfortable" and the ripening cycle for example is a little bit more uneven but a little bit longer.

From the perspective of the Consejo Regulador... the organism that in each Denomination of Origin is in charge of telling the consumer how the wines made in that same area are going to be and that they want that same consumer to consume... well, they are almost always very good XD. In their defence it must be said that it is true that wines in almost any part of the world are becoming more and more correct as there are better and better winemakers, who know more and better how to do their job, have more means and more knowledge. But we are well aware that the climate is not necessarily being more benign with our vineyards, so these average scores are often not really representative.

Finally consumers end up understanding if the vintage is good by knowing the area and the specific producer they are talking about, and the factor that ends up giving them the most information is usually the price. Not so much for quality in the strict sense of the word, but rather for the concept of supply and demand. And as Manuel Manquiña said in Airbag (Juanma Bajo Ulloa 1997) "the concept is the concept". Good quality vintages tend to be somewhat more expensive. Bad vintages of production, also tend to be more expensive. Good vintages, if they are short, tend to be twice as expensive.

In which wines the vintage is especially key?

The question is biased because it implies that for some it is not. But without being papist, there are styles of wine where it is, if possible, more relevant. In simpler (but not worse) styles of wine, there may be more fruit or more alcohol in one vintage than another, but in general there will be little change (from the consumer's perspective at least).

In the world of sparkling wines for example, let's think of the Mediterranean arc, in the Penedés area specifically where we make some of the best sparkling wines in the world, we enjoy a warm climate but tempered by the proximity to the sea, where we can have full maturation every year and make a wine every year. However, in areas such as Champagne, one of the northernmost vine-growing regions and therefore one of the harshest for the plant, not every year we enjoy weather conditions that are pleasant enough to bring the grape ripening to the point where it is needed to make great wines. In areas like this the vintage qualification (which you can find on their labels as Millesime or Vintage, referring to the year) is reserved only for those great years and great wines that are truly considered capable of transcending time and that do not require any blending with wines from other years.

The search for the winning horse

But if there is one family of wines where nobody wants to speculate on vintages, it is with the... expensive wines. Joking aside, it is true that the great historic wines, the great winemaking areas, what we know as "fine wine", we are much clearer about the best and worst vintages, or at least we know better the identity of the vintages, especially because we have many more specialists year after year, for many years, tasting, comparing, and buying. We are talking about the more or less accessible incunabula: the Grand Crus Classées of Bordeaux, the small vineyards of the big names of Burgundy, the historic Riojas, the star winemakers of Piedmont, Tuscany or Napa, or the proper names like Vega Sicilia.

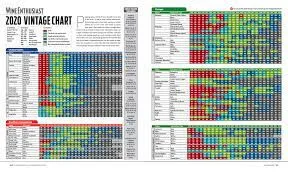

In this case the easiest thing to do, if you don't have the necessary experience, is to refer to the vintage tables. They tell you which are the most interesting vintages to buy, drink or keep. If you want to know specific information about different areas to know where it might be interesting to look for, we leave you one of the Vintage Chart (something like a vintage report) that we like the most, which is published every year by cdn.wineenthusiast.com. Here you can also see a summary of mythical vintages from each area

Either way the bad news or the good news is that as you know in wine, 2 + 2 never equals 4. Sometimes it is interesting to try vintages with more modest scores from trusted winemakers and find not only great wines, but also good bargains.

https://www.wineenthusiast.com/newsletter-signup/2020-vintage-chart/download/2020_Vintage_Chart.pdf

Year 2020: CoVid 2019. What to expect from the vintage in which everything changed.

We wanted to talk to some of the protagonists so they could tell us how the vineyard is experiencing the most convulsive vintage in living memory.

Jorge Navascués, winemaker at Bodegas Contino and Pago de Ayles and consultant in other areas such as Navarra with Viña Zorzal or in Valdeorras with the same CVNE group (and his own projects in Requena or Cariñena), has a very complete vision of the temperature of the harvest. "This has been a very complex year, and above all heterogeneous, the difference between plots or different areas is very important. Health, due to the high rainfall and mildew, and ripening with an early but very long cycle have been key". Jorge tells us that these irregularities have meant that in Contino, for example, plots of red have been planted before white. In spite of everything, he says, "Those winegrowers who have overcome the mildew and harvested on time will have an interesting vintage, with good acidity and wines to last over time thanks to the complexity of the year.

Agusti Torelló Roca, one of the youngest faces of Penedés and Montsant, but with decades of accumulated experience in the family and a precise and respectful perspective of both the vineyard of his native Penedés and its sparkling and still wines. "An early start to the cycle due to an overly mild winter and almost constant rainfall until the beginning of the summer was compounded by a very dry summer." He compared the current vintage with 2018 where there was also quite a lot of rainfall and mildew but he gave us a clue, two years ago a cold winter helped the cycle to start later, the plant to set weakly, and therefore it was not so damaging.

.

We have also heard the version of someone who still remembers with a shudder the extent to which a winegrower can be defenceless in the face of bad weather, "the frost at the end of April 2017 left us with a blank year". Alberto Pedrajo and Javier Trigueros, at the helm of Alonso y Pedrajo, a small gem of a winemaking project in Villalba de Rioja, have seen in their short time on their own estate the hardest aspect of exposure to the vicissitudes of a vintage. In this 2020, already a rough year, Alberto tells us that it has been a roller coaster "a year of a lot of countryside, where we have had to be very attentive, a lot of vigour, a lot of water and all that that entails". Despite this, he advises us not to lose sight of the white wines (his always leave mouths agape), and he predicts a year of exceptional Rioja whites.

Alberto Pedrajo and one of his babies at the finca La Cala

We hope that this vintage will be the beginning of another great one and that the work of the growers and winemakers will make us remember this year not only because of that damn bug (and I don't mean mildew).

Did you know that

Harvesting in the southern hemisphere takes place between February and April, just the opposite of the northern hemisphere vineyards.